Written by Aranka Bijl, Sietse Brands & Michaela Arztmann

Remember the time when you had to learn multiplication in school and needed to drill all the tables from 1 to 12? It was quite boring, right? Ms. Johnson thought so too and she was looking for a more enjoyable experience to teach her students. In this blog we'll show you how she combined game mechanics and formative assessment in practice.

Games are a popular didactic method that has been widely implemented in educational contexts. As such, games are known to support learning outcomes [1], and to contribute to students’ motivation and engagement [2, 3]. Moreover, since games provide an adaptive environment where failure is accepted [4], they are able to reach each student equally and can even increase the social participation of students in a classroom [5].

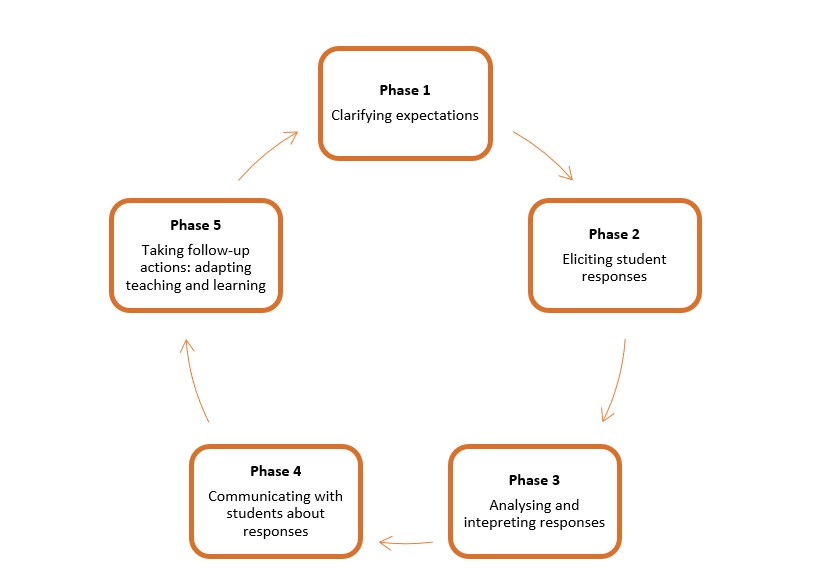

So, games can be a valuable addition to classroom practices. Then the question becomes: where in the curriculum do games fit best? There are many possibilities for using games in the classroom, for instance 1) as an instructional tool, 2) to foster collaborative learning, or 3) as a low stake assessment of student understanding and learning progress. The latter is often referred to as formative assessment. We argue that the potential of games is best aligned with formative assessment. More specifically, the different features of games can be implemented into the formative assessment cycle (FAC) [6]. The FAC introduced by Gulikers and Baartman (2017) consists of five phases, illustrated in Figure 1. The FAC is a way of designing a practical and iterative formative assessment cycle in a classroom. This gives the teacher the opportunity to address different learning needs of students.

Figure 1. The formative assessment cycle. Adapted from Gulikers and Baartman (2017).

Gamifying elements of classical teaching is easier than it seems and may yield similar results if done right. There are five common mechanics that games often include, all directed at motivating a player to keep playing and improving.

The first mechanics are scoring points. Points are what drives a gamer to give moving forward. Points are the reward for performing actions right. One could argue that points are already at the heart of education in the form of grades. But points in a game are of a much lower stake than grades. Points are a method of giving feedback: a gamer doesn't receive any points when an action was performed incorrectly or not in time, but may even get bonus points when it was done exactly right. In addition to points, also leaderboards are a way of gamifying. With leaderboards, competition is introduced as players can compare their points to the scoring of other players. A sense of competition can be healthy, but especially in primary school one should be wary of comparing of high and low achievers. One way to counter that could be the introduction of levels. With levels, additional difficulties are introduced to a game. If a player is able to finish a level he could progress to a more difficult level, providing more complex challenges and different contexts. The final gamifying mechanics are the introduction of challenges and badges. With challenges, additional ways of playing the game are introduced. Badges are rewarded for completing these challenges.

Let's apply the FAC phases and game mechanics to an elementary school classroom setting.

We have Ms. Johnson with her fourth graders who are in the midst of learning multiplication. Now, in order to motivate students to practice and gain insight in their progress and understanding, Ms. Johnson created a game for students to play. Students play this game in pairs, using cards. On these cards, math problems are presented. Students draw cards in turns, one solves the answer while the other one observes and checks the answer, giving immediate feedback. Students have a ‘dashboard’ on which they can keep track of their score. This simply is a paper with a progress bar from 0 to 20. A good answer leads to the coloring of the next point in this bar. At the end of the game scores are compared and a winner is declared. To see individual progress, scores are also compared to previous game iterations using a similar but personal dashboard tool. Students can earn decals for simple challenges: playing the game three times in a week earns a decal on the personal dashboard. There are additional decals to be earned for playing against everyone in class, improving three consecutive games, etc. Levels are also available, cards are color coded, with red cards having more complex problems than green ones. This game had Ms. Johnson's students enjoy their practice while gaining a lot of feedback. Ms. Johnson gained insight in student's learning progress and was able to signal issues using the personal dashboards, allowing her to adapt her teaching instructions accordingly.

The observant reader may recognize the phases of the formative assessment cycle in this example. Using the five game mechanics and the formative assessment cycle it can be quite easy to create fun and insightful practice opportunities which also serve your own teaching practice. Game on!

References

[1] Wouters, P., Van Nimwegen, C., Van Oostendorp, H., & Van der Spek, E.D. (2013). A Meta-Analysis of the Cognitive and Motivational Effects of Serious Games. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 249-265. https://doi.org/10.2196/18644

[2] Lamb, R.L., Annetta, L., Firestone, J., & Etopio, E. (2018). A meta-analysis with examination of moderators of student cognition, affect, and learning outcomes while using serious educational games, serious games, and simulations. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.040

[3] Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S.K.W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C.J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100326

[4] Plass, J.L., Homer, B.D., & Kinzer, C.K. (2015). Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psychologist, 50, 258-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

[5] Hanghøj, T., Lieberoth, A., & Misfeld, M. (2018). Can cooperative video games encourage social and motivational inclusion of at-risk students?. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49, 775-799. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12642

[6] Gulikers, J. T. M., & Baartman, L. (2017). Doelgericht professionaliseren. Formatief toetsen met effect! Wat DOET de docent in de klas? Eindrapport NRO-PPO overzichtsstudie dossiernummer 405-15-722. NRO. https://edepot.wur.nl/440065